The recently opened Shan Sum Columbarium in Hong Kong provides a final resting place for thousands of people in one of the most densely populated cities in the world.

It features a magnificent 12-story tower with a white marble lobby and luxurious chandeliers, giving the impression of a luxury hotel.

Due to Hong Kong’s crowded neighborhoods and a shortage of urn spaces, bereaved families used to face years of waiting to secure a place for their loved ones’ ashes. To alleviate this problem, the government implemented a decade-long effort to involve private companies in the death care sector, establishing places like Shan Sum.

Ulrich Kirchhoff, a German architect, incorporated natural elements into the high-density space of the sleek, contemporary building to create a tight-knit neighborhood feel.

Kirchhoff incorporated undulating lines, greenery, and carved rock textures into the Columbarium’s design to evoke traditional Chinese cemeteries perched on mountain slopes.

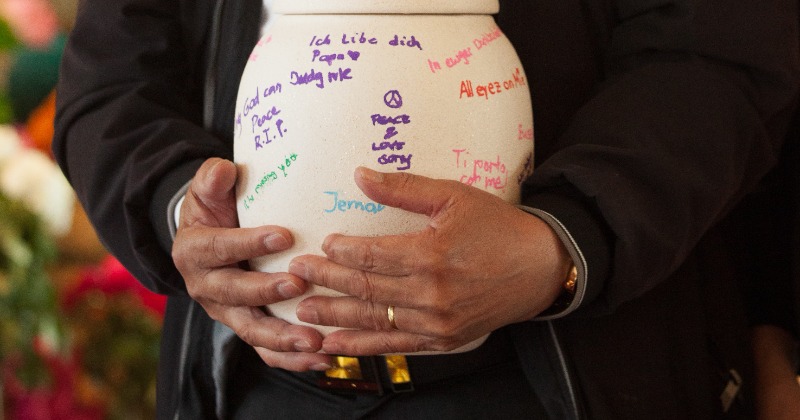

Inside the air-conditioned chambers, ashes are stored in ornate compartments, which vary in size, some as small as 26 by 34 centimeters (10 by 13 inches).

Unsplash

Unsplash

Rooms on each floor are specifically designed for privacy, as opposed to cramped public columbariums that feel like warehouses.

However, renting a unit at Columbarium is expensive, similar to the cost of apartments in Hong Kong, making it inaccessible to most people.

Prices range from $58,000 for a two-person prime option to nearly $3 million for a premium family package.

Considering that the average monthly household income in Hong Kong is around $3,800, these prices put the units out of reach for many people.

A shortage of urn space in Hong Kong led to cremated remains being stored for years in unlicensed funeral homes or columbaria inside temples or restored factory buildings.

Historian Chau Chi-fung attributes this crisis to the lack of a comprehensive government policy for dealing with cremated remains, which originated during the British colonial administration before the handover of the city to China in 1997.

Cremation became popular in Hong Kong in the 1960s, and approximately 95 percent of deaths now result in annual cremation. Changing social norms have contributed to this shift from traditional burials.

The government projects a 14 percent increase in deaths by 2031. Still, officials say the city is poised for the increase, with about 25 percent vacancies among the current 425,000 public columbarium sites and plans to supply additional public and private.

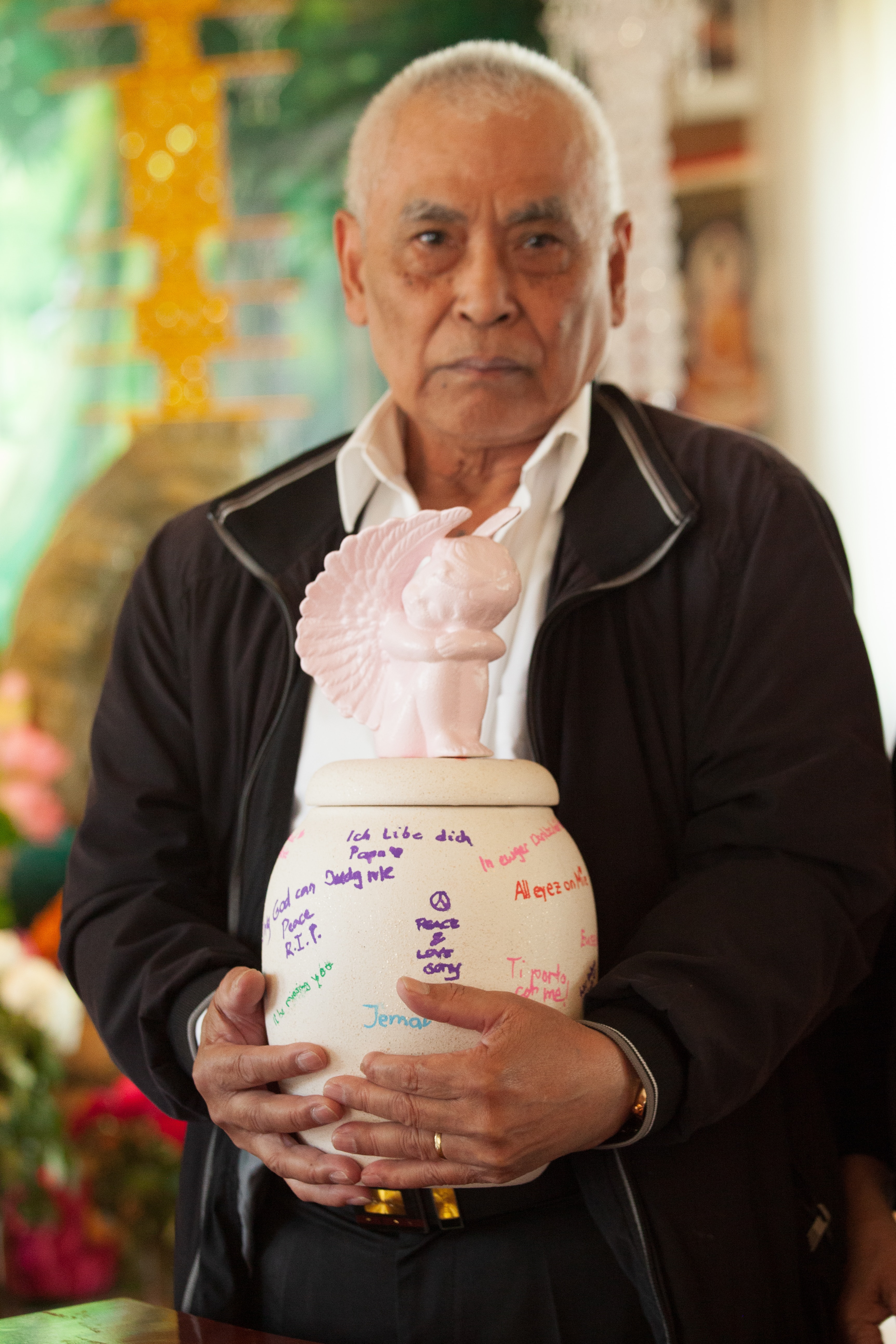

Wing Wong, who entombed his father in the Tsang Tsui Columbarium, notes the improvement in his experience compared to previous horror stories.

He praises the availability of a place for his father’s ashes, emphasizing the importance of not enduring uncertain waiting periods. Wong’s family chose the government-run location because of its favorable feng shui and affordable prices, in line with his father’s desire for an ocean view.

Despite efforts to address the problem, Chau acknowledged that there is still a shortage of polling place space in Hong Kong.

(With AFP inputs)

For more trending stories, follow us on Telegram.

Categories: Trending

Source: vtt.edu.vn