Nobel laureate Louise Glück, a poet of unwavering candor and insight who wove classical allusions, philosophical reveries, bittersweet memories and humorous commentary into indelible portraits of a fallen and heartbreaking world, has died at age 80.

Glück’s death was confirmed on Friday by Jonathan Galassi, his editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

He died of cancer at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, according to his publisher.

A former student of Glück, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jorie Graham, said the author had recently been diagnosed.

“I think it’s very like her that she only found out she had cancer a few days before she died from it,” Graham said. “All of her sensitivity, both on and off the page, was cut so close to the spine of time.”

In a career spanning more than 60 years, Glück forged a narrative of trauma, disillusionment, stagnation and longing, marked by moments, but only moments, of ecstasy and satisfaction.

In awarding him the literature prize in 2020, the first time an American poet has been honored since TS Eliot in 1948, the Nobel judges praised “his unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

Glück’s poems were often short, one page or less, examples of his attachment to “the unsaid, to suggestion, to eloquent and deliberate silence.”

President Barack Obama awards Glück the 2015 National Humanities Medal for her “decades of powerful lyric poetry that defies all attempts to label it definitively.”

Influenced by Shakespeare, Greek mythology, and Eliot, among others, she questioned and sometimes outright dismissed the bonds of love and sex, what she called the “premise of union” in her most famous poem, “Mock Orange.”

In some ways, life for Glück was like a troubled romance, destined for unhappiness, but meaningful because pain was our natural condition, and preferable to what she assumed would come next.

“The advantage of poetry over life is that poetry, if sharp enough, can last,” he once wrote.

In her poem “Summer,” the narrator addresses her husband and remembers “the days of our first happiness,” when everything seemed to have “ripened.”

Then the circles closed. Little by little the nights became colder;

the hanging leaves of the willow

It turned yellow and fell. And in each of us it began

a deep isolation, although we never talk about this,

of the absence of repentance.

We became artists again, my husband.

We could resume the trip.

In some ways, life for Glück was like a troubled romance, destined for unhappiness, but meaningful because pain was our natural condition, and preferable to what she assumed would come next.

Pulitzer-winning poet Tracy K. Smith said in a statement Friday that Glück’s poetry had “saved” her many times.

“I constantly think of these lines from ‘The Wild Iris’: ‘At the end of my suffering / there was a door.’ And from these lines from ‘The House in Marshland’: ‘The darkness dissipates, imagine, during your lifetime.’ It is as if her spare, patient syntax forms a path to and through the weight of life,” she wrote.

Glück published more than a dozen books of poetry, along with essays and a short prose fable, “Marigold and Rose.” She drew on everything from Penelope’s weavings in “The Odyssey” to an unlikely muse, the Meadowlands sports complex, inspiring her to ask: “How could the Giants name that place Meadowlands?” It has as much in common with a pasture as the inside of an oven would have.”

In 1993, he won the Pulitzer Prize for “The Wild Iris,” an exchange partly between a beleaguered gardener and an uncaring deity.

“What is my heart to you/that you must break it again and again?” the gardener asks. The god responds: “My poor inspired creation… In the end you are/too little like me/to please me.”

Influenced by Shakespeare, Greek mythology, and Eliot, among others, she questioned and sometimes outright dismissed the bonds of love and sex, what she called the “premise of union” in her most famous poem, “Mock Orange.” via REUTERS

His other books include the collections “The Seven Ages,” “The Triumph of Achilles,” “Vita Nova” and a highly acclaimed anthology, “Poems 1962-2012.”

In addition to winning the Pulitzer, he received the Bollingen Prize in 2001 for lifetime achievement and the National Book Award in 2014 for “Faithful and Virtuous Night.”

She was poet laureate of the United States in 2003-2004 and received a National Humanities Medal in 2015 for her “decades of powerful lyric poetry that defies all attempts to definitively label it.”

Glück was married and divorced twice and had a son, Noah, with her second husband, John Darnow.

He taught at several schools, including Stanford University and Yale University, and viewed his classroom experiences not as a distraction from his poetry but as a “recipe for lassitude.” Students would remember her as demanding and inspiring, not above making someone cry, but she was also valued for guiding young people in finding their own voices.

“You would hand something over and Louise would find the one line that worked,” poet Claudia Rankine, who studied with Glück at Williams College, told The Associated Press in 2020. “There was no room for the subtleties of mediocrity, nor for falsehoods.” praise. When Louise speaks, you believe her because she does not hide in civility.”

Originally from New York City and raised on Long Island, New York, she was of Eastern European Jewish descent and heir to an everyday creation not associated with poetry: her father helped invent the X-Acto knife.

His mother, Glück would write, was the family’s “moral leader of the whole family,” the one in whose evaluation of his stories and poems he looked above all others.

Glück was also the middle of three sisters, one of whom died before birth, a tragedy she seemed to refer to in her poem “Parados”.

A long time ago I was wounded.

I have learned

exist, in reaction,

out of touch

with the world: I’ll tell you

what I wanted to be –

a listening device.

Not inert: still.

A piece of wood. A stone.

Describing herself as born to “bear witness,” Glück felt at home with the written word and considered the English language her gift, even her “inheritance.”

But as a teenager, she was so intensely ambitious and self-critical that she waged war on her own body. She suffered from anorexia, dropped to 75 pounds and was terrified of her mortality.

His life, creative or not, was saved after he decided to see a psychoanalyst.

“Analysis taught me how to think. “It taught me to use my tendency to object to ideas articulated about my own ideas, it taught me to use doubt, to examine my own speech for evasions and splits,” he recalled during a 1989 lecture at the Guggenheim Museum. “The more I retained my conclusions, the more I saw. I think I was also learning to write.”

Glück was too frail to become a full-time college student and instead attended classes at Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University, finding mentors in the poets and professors Leonie Adams and Stanley Kunitz. When he was in his twenties, he published poems in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and other magazines.

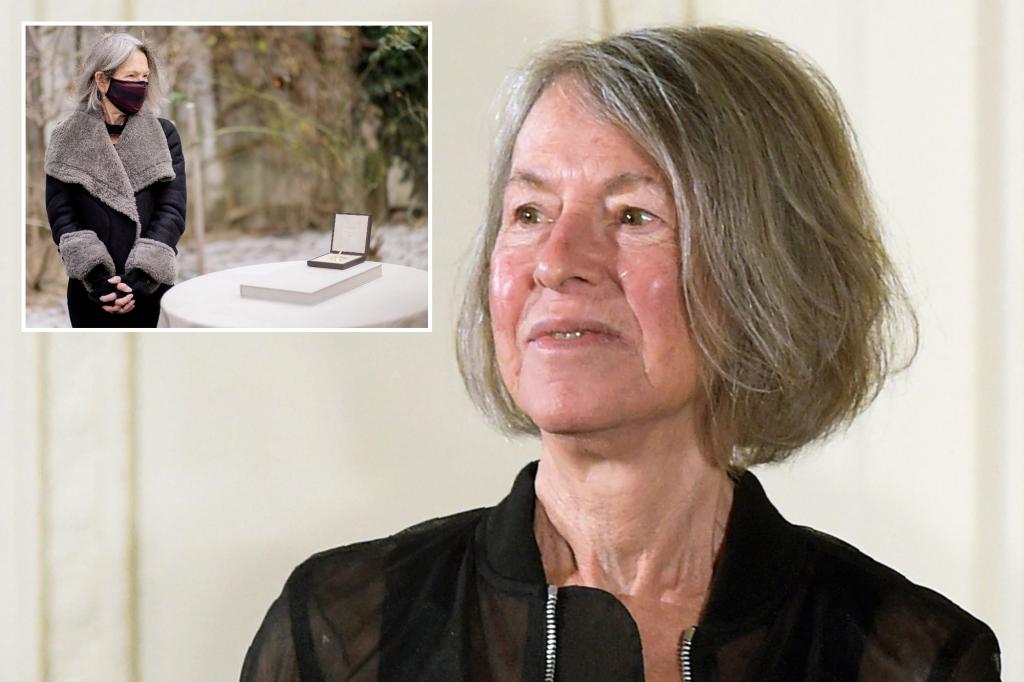

Glück next to his medal and his Nobel Prize in Literature diploma in front of his home in Cambridge in 2020.REUTERS

Glück’s first book, “Firstborn,” was published in 1968 and preceded a long period of writer’s block that ended while he was teaching at Goddard College in the early 1970s.

He once believed that poets should avoid academia, but found contact with Goddard students so enriching that he began writing poetry again, work he considered far beyond the “rigid interpretations” of “Firstborn.”

From his silence he discovered a new and more dynamic voice.

His second book, “The House on Marshland,” was published in 1975 and is considered his breakthrough.

But he continued to suffer years of what he called “brutal punitive blankness,” as he tried everything from gardening to listening to Sam Cooke records to escape.

Later books like “The Wild Iris” and “Ararat” became testimonies of a personal and creative reinvention, as if his older books had been written by someone else.

“I’ve always had this kind of magical thinking of detesting my previous books as a way to move forward,” he told Washington Square Review in 2015. “And I realized I had this feeling of sneaking pride. in achievement. Sometimes I would just stack my books and think, ‘Wow, you haven’t wasted all your time.’ But then I was really scared because it was a whole new feeling, that pride, and I thought, ‘Oh, this means really bad things.'”

Categories: Trending

Source: vtt.edu.vn